The Work of Art / The Art of Image

“Art pieces and process shots are the same—this is the Arte Povera concept. What you made is what it is. And the way you made it is as important as the finished piece.”

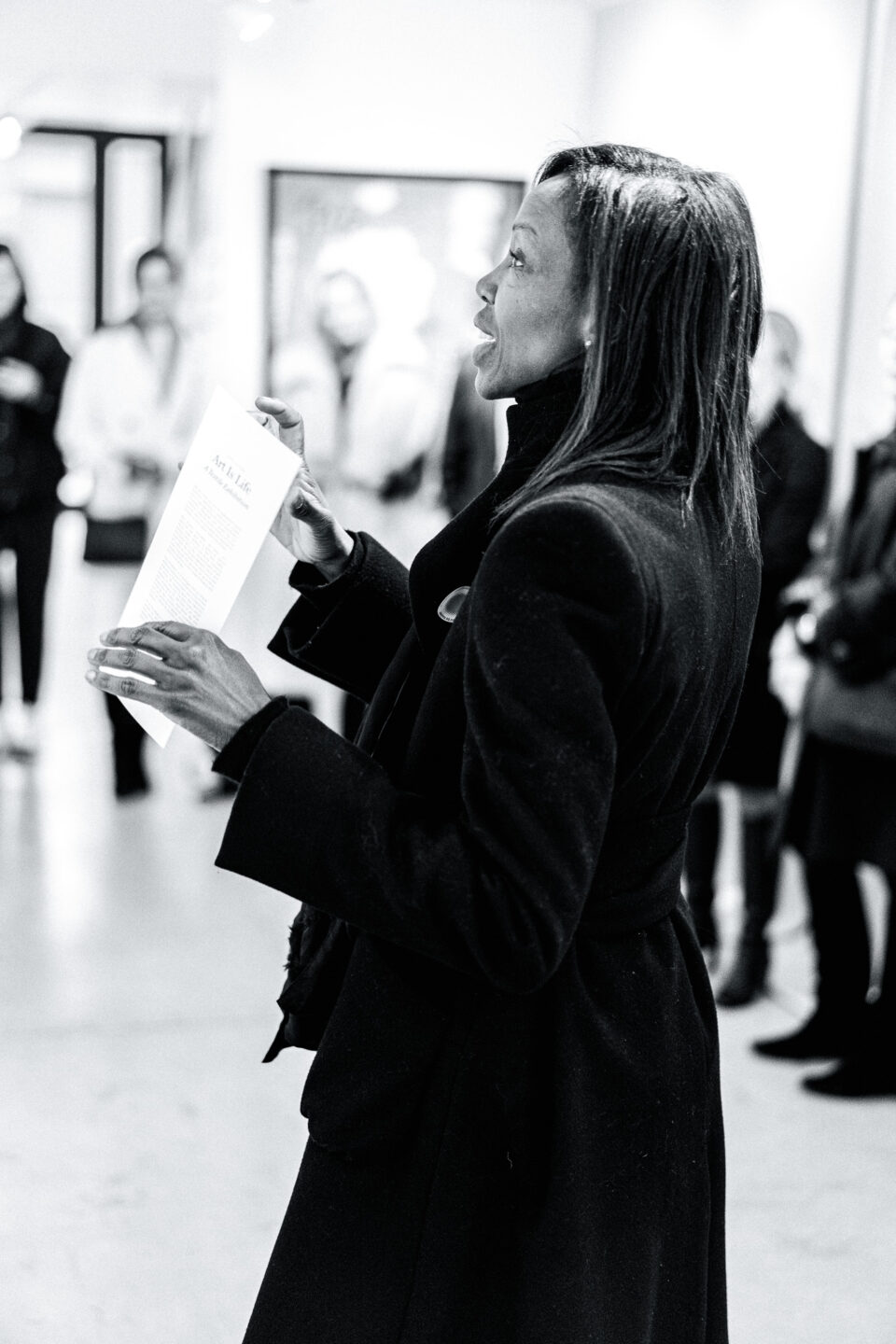

— Sylvie Johnson, Artistic Director

The phrase “Art is life” can be interpreted in different ways. One could interpret it as meaning Art is the lifeblood of existence, the obsession of life; perhaps the most natural or immediate interpretation, given the pervasive if not overdramatic use of “___ is my life.” One could interpret “Art is life” to be an allusion to Art’s role of revealing otherwise inexpressible conditions of the human experience and what it is to be, as a human; Art as the experience of life itself, highlighting even the most infinitesimal or inexpressible aspects of existence. Or, as was an interpretation of the Arte Povera artists, it could draw attention to the fact that Art itself is alive, changing along with its people and environment, becoming in the process of its making. Perhaps this subconscious understanding of Art’s “aliveness” is why we call even finished pieces of art “works”—to denote their active and constant becoming, even after completion; to bring attention to the fact that the process—the work—is itself, in some cases, the piece. Perhaps, for the Arte Povera artists, “Art is Life” meant all three.

A few weeks ago, alongside Déco Off, we put on a four-day exhibition in the small Galerie Alain le Gaillard of Paris. Those of you who have visited our Gallery in New York may have noticed a different atmosphere walking into the Galerie Alain le Gaillard. Upon stepping through the glass doors of our New York Gallery, you are met with an array of colors (currently a flood of watercolor pastels) and are drawn into walking the long hallway of natural light to experience each rug and colorway through sight and touch. However, upon entering the Galerie Alain le Gaillard, you find yourself not in a soft, prismatic array of colors, but instead surrounded by a zephyr of green.

Before experiencing the Nymphea exhibition in the Galerie Alain le Gaillard, many of us first explored the Jeu de Paume’s Renverser ses Yeux (Reversing the Eye) exhibit (and some of you may have been joined by artistic director Sylvie Johnson). A full experience of Arte Povera’s spirit, both original and contemporary, the Jeu de Paume and LE BAL presented the collaborative exhibition in four chapters: “Body” (at LE BAL), “Experience,” “Image,” and “Theatre.”

Upon the exhibits’ close, I spoke with Sylvie about Renverser ses Yeux and the Galerie Alain le Gaillard curation.

With such a range of artists and works in Renverser ses Yeux, did you gravitate toward any one piece or group of pieces?

Not at all. Because it is a whole… Jeu de Paume specializes in photography and video, so that was the angle they took for the exhibit, and that was a way to understand Arte Povera through the different artists together. Not one, but together—as a whole.

What was the significance of the Jeu de Paume’s curation being centered around photography and video?

Well, in all of the Arte Povera artists, some made photographic work—many of them, even, like Penone—some made installations with images… so [the exhibition] was all of those works based on images: photographs they made, the work they do, installations with video and sculpture. But in Arte Povera, there were also a lot of performances, and those performances were photographed and filmed, so if you go through the catalog of work that they did, you will see all the angles of this ‘image’ work that were so important in Arte Povera—thoughts that even started in the [Kunsthalle] Bern exhibition in Switzerland, of [Harald] Szeemann. The work in progress was seen, visible.

Are a lot of the photographs in Renverser ses Yeux considered process shots, then?

No no no, they are art pieces. Art pieces and process shots are the same—this is the Arte Povera concept. What you made is what it is. And the way you made it is as important as the finished piece. It was mostly art pieces that came from collections: some photographs that Penone did, a photograph of Fontana taken by another Arte Povera artist, some photographs of a happening that happened in another exhibition, some movie of [Michelangelo] Pistolleto rolling his newspaper ball in Turin, which was really well known as a happening… and alongside that, you have a glass work, like a piece, what is more traditionally thought of as art. But everything was a piece. What I am saying is that the videos are pieces as well, even if they also show the work in progress of a piece. It is the process that is the piece, but you must capture it somehow if it is not being done right there in the gallery.

Would you say the process of the work is a separate piece from the finished work?

No, these are not separate pieces. It’s the whole. This is why you can’t say, “I like this, I like that,” it’s a whole, together. All of the exhibit is a whole: it’s about what Arte Povera is.

So the exhibit was more about the spirit of the movement, versus trying to highlight individual artists or pieces?

The pieces are highlighted too, but it is really the spirit of the movement. Some artists made sculptures, and at the same time, made pictures, and drawings. Penone is one of them—his drawings are in the Pompidou, but you also have photographs that he made, and a plaster sculpture of his chest with a projection of his kin on top. But these are art pieces. All of these are art pieces. What I’m saying, though, is that [the Jeu de Paume] chose, because [their focus] on photography and video, more photography and video. And even pieces where people are involved—you have a lot of pieces like that in the exhibition—it is with the angle of what an image can be. Even if it’s a coffee table with some pieces, sure it’s an installation, but in the meantime it’s an image.

How do you mean, “in the meantime it’s an image”?

Because when you see something like that, when you see an installation, you are not going back home with the installation or the happening—it’s something that you have in your mind. It’s an image you keep with you, in your mind.

That’s not the purpose [at the Jeu de Paume], though; the angle of the museum is to promote photography, videos, modern sculpture. The thing that people need to remember is that Arte Povera is really a world. It’s not really one principle like, “oh, he’s a painter.” It’s Arte Povera: he’s a painter; he can draw; he can make video; he can make sculpture. This diversity of the movement that what is interesting. And this is why there were so many exhibitions that were so different. These artists have different mediums and show that art can use different principles, not just the classics that we know, like painting, drawing, sculpture; it’s more open than that. Each of those artists made different pieces using that mentality.

It was about how they made those images that is important, and why they made it, and how those images are a part of the general art. It’s super complex as an exhibition. Even me, I went to see it four times. I know a lot of those artists, but it’s not an easy… Arte Povera is not an easy movement. What we talk about, what we show, is 10% of what it is.

Were the Je de Paume exhibition and our own exhibition related in any way through curation?

No, not at all. Our exhibition was not a bridge to theirs. Our exhibition was my conception of what the spirit of Arte Povera can be, related to textiles, to what we do. It’s not a translation—of Renverser ses Yeux or of any Arte Povera work, directly. But the exhibition was good for others to see, to understand the complexity of the movement, and to see that there are no differences between art. To understand what we’re doing is art at the same time.

How would you compare the experience of walking through the New York Gallery to that of walking through the Galerie Alain le Gaillard exhibit?

First, it’s a question of space. The New York Gallery is 500 square meters: wonderful for us to see the palette of colors for the collection and how they work together.

In Paris, it was to show an instance. It’s Arte Povera, a happening. Four days of happening with a monochromatic curation in this small space. Since the beginning we have done this, not just because of Arte Povera—since the beginning, all of our small exhibitions have been monochromatic, not only because the pieces are monochromatic, but because this presentation gives you a better understanding of them. The principle is, in a small gallery in Paris, to be immersed in a cocoon—because there is so much going on in a cocoon—and to be able to see more in the details without being distracted.

Wrapped in a spring-hued cocoon—transformative.

Each work, like the Arte Povera artists’, has three essential, individually unique components that contribute to its experience: the process of the making, the everyday materials (given a spotlight under which we can see their own art), and the interaction and participation of the person experiencing it.

Each piece is a piece of living art: alive in its creation and alive in its constant, changing experience.

This is what it means to cultivate a virtuous circle with pieces that bring as much joy and pleasure to the maker as to the receiver.