Ideas Not My Own

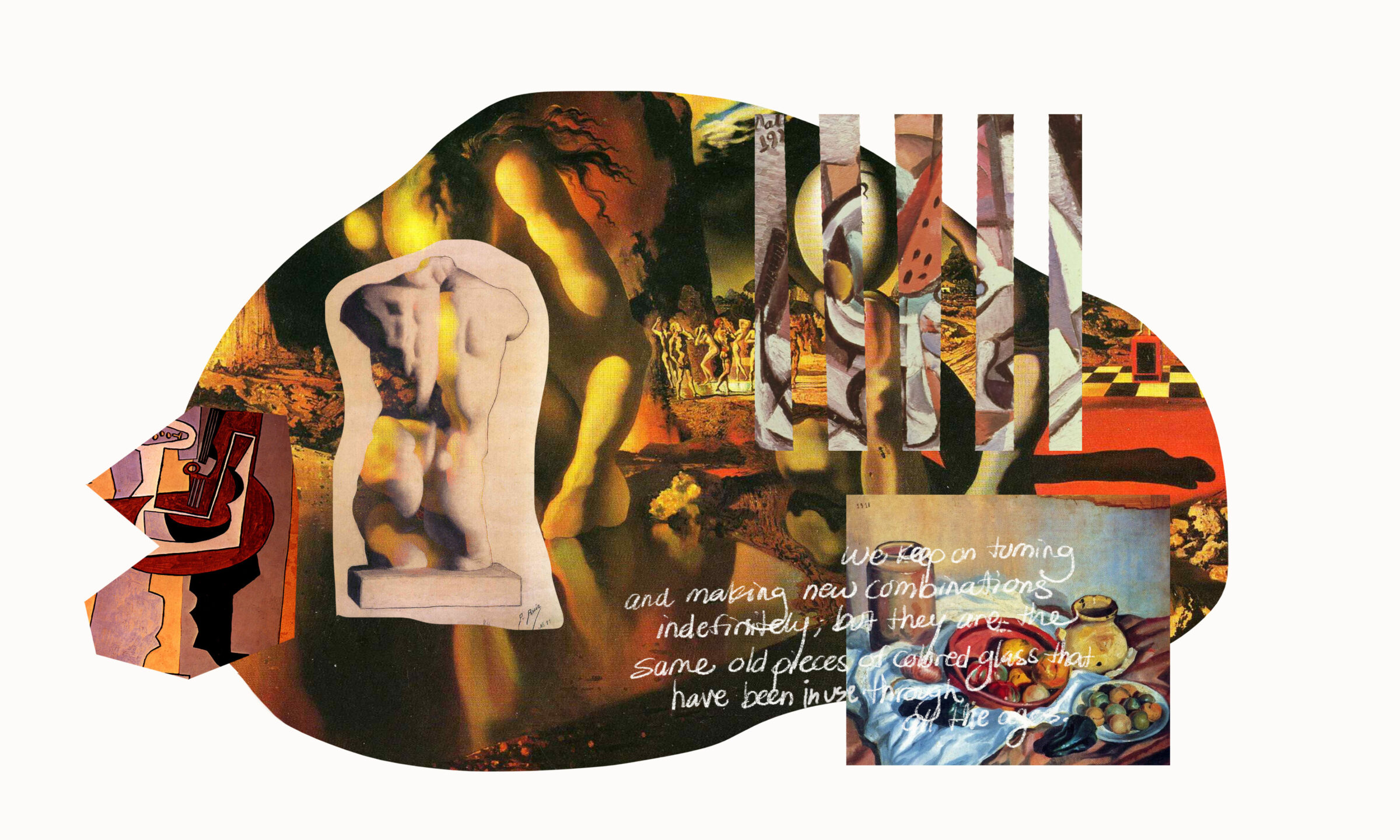

“There is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope. We give them a turn and they make new and curious combinations. We keep on turning and making new combinations indefinitely; but they are the same old pieces of colored glass that have been in use through all the ages.”

— Mark Twain, Writer

In grade school, we are taught over and over again to learn the rules and follow them. Why do you bother learning all of these grammatical rules and syntactical regulations? To regurgitate facts? Of course not. Though that may be the exercise to learn them in the beginning, you learn these rules so that you can use them as tools to communicate your own perspective.

It’s easy to think about in terms of art: a painter does not learn brush strokes and perspective to continually paint still life studies for the rest of his life. A painter learns brush strokes and perspective so that he has the tools to express his own vision. He learns the fundamentals so that he knows what brush strokes achieve what effects, which colors harmonize and which vibrate, and what impact all of these things have on the viewer. He learns so that he can then, like understanding rhythm or punctuation, just as readily deviate from these rules to bring different but intentional attention to each element’s role in a piece.

As a wise artist once said, “Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

Design—like many things in life—is a lot like a term paper. As you walk through the world, you accrue bits and pieces of information, knowledge, and inspiration, hoarding some and discarding others; unknowingly storing some away for a rainy day. Each piece you gather adds a layer to your lens; each experience, each piece of knowledge, each broadening, creating a more complex eye for you to look through.

There is one clear difference between a graduate term paper and a grade school research paper: one has a voice and the other doesn’t. Grade school research papers regurgitate facts. Term papers are the opportunity to look at everything you’ve learned; curate it; and synthesize it, framing your uniquely-gathered materials in your uniquely-formed perspective.

Unique perspectives and recognizable voices are often the things studied in great works of literature, film, and art, but seldom do these studies spell out the secret to success.

Strunk and White will refer you to any one of a hundred niche and situation-specific questions regarding punctuation and capitalization; The Norton Field Guide will help you find the perfect structure for your paper. But there is no book telling you step-by-step how to develop your voice—let alone how to use it.

Just like you once learned to speak—watching, listening, practicing—your creative voice develops over time. As you move through the world, creating and absorbing your own unique cocktail of experiences and interests, you slowly develop into yourself, with a distinct system of thought and a unique pair of eyes—a pair of eyes no one else in the world will have except you.

“There is no such thing as a new idea.” This statement can be so abrasive because it makes you, as a creative, feel as though you are only ever a simple thief. Though the delivery of this phrase is pessimistic, however, it rings reliably true.

An idea is never truly only your own; but that simply means that even you, and your ideas—like the world around you—are made up of innumerous people, thoughts, experiences, and ideas. Born in different times, in different places, to different experiences, with different hearts, each person is not only made up of all of the people, thoughts, experiences, and ideas they encounter but is also a unique, unrepeatable mixture of these select things. No two cocktails are ever exactly the same.

So yes, so many of the pieces of your creation were stolen—gathered from somewhere else, from some other time, and conjured at the moment of creation.

But each of those pieces was carefully selected by you—and filtered through the unique cosmos that lies behind your eyes.

This seemingly abrasive statement is not a pessimistic critique; it is a reminder that our ideas are as much a harmonious, symbiotic ecosystem as the world we inhabit is.

Like term papers, the arts are our chance to express our unique perspectives. Mixed in with all of the citations and references of an idea is the other, possibly more central piece: your voice.

You feed and cultivate the ecosystem of your mind with the array of materials and experiences you find in the world, then synthesize them in ideas to support your persuasive point of view. This idiosyncratic vantage point comes about as you curate in your mind, choosing the best-fitting pieces to build out the image, and leaving the rest behind. The lens you look through is the unique Ariadne’s thread stringing the picture together.

Building on the past is not theft; it is inevitable and essential.

It is how we move forward.