Chromatic Echoes

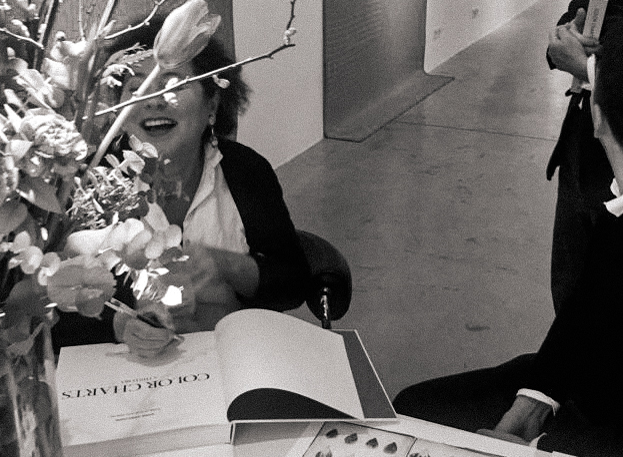

Merida’s Beginnings exhibition at the Galerie Alain le Gaillard was on show for five days in January of 2024. In this exhibition, the studio showcased six artist’s proofs in Lava from the Outside Within series in conversation with a set of constructivist and biomorphic paintings from the 1920s and 30s from Galerie Alain Le Gaillard and Galerie Le Minotaure. Accompanying the exhibition’s debut, anthropologist Anne Varichon provided opening remarks on the profound significance of color throughout human history. Through the lens of Sylvie Johnson’s work, Varichon’s talk explores how color can evoke memory, emotion, and a sense of connection with the world. In her words, Johnson’s artistry is depicted as a bridge between past and present, infusing everyday objects with beauty and meaning, and inviting contemplation of the timeless essence of color. Anne Varichon’s book Color Charts: A History is now available in English through Princeton Press. The transcription of Varichon’s talk follows.

Color doesn’t satisfy hunger, it doesn’t warm you up, it doesn’t allow you to kill or even defend yourself. But it has been with humanity since its earliest beginnings—because it’s a sign. Because it lies at the heart of the privileged harmonies that define a culture in the eyes of others. Because it is a “given to be seen” with which to build a wordless dialogue between members of the same community. The color of fabrics thus affirms, “You were born son of the chief,” or “My existence rubs shoulders with the divinities,” or “I come from afar, I am a foreigner.”

Above all, color is a source of infinite human pleasure.

For millennia, color has been alive, drawn from living things: plants, insects, shells, minerals. It has also drawn its strength from the impetus and care that gave it birth: in-depth knowledge of an environment’s resources, skills of absolute simplicity or immense refinement, heritage, matrimoine, handed down over the centuries, often without written support.

Total respect for the color-makers who have gone before us, an anonymous crowd with humble yet powerful gestures, inspired and attentive, who knew how to infuse color with a full, complete intention. And respect in particular to those who were at the origin of textile color—that textile which, from diapers to shrouds, remains close to the body, not far from the soul!

Clothes and even fabrics in our environment are the site of non-mental, intimate, archaic experiences that are deeply imprinted on our psyches. A fresh blue sheet or an enveloping red shawl are like Proust’s madeleines, conjuring up memories and emotions, just like the wind-blown curtain with its moving lights and shadow puppets, the cinema of our childhood imaginations.

Colors are innumerable, but there can be a quality to colors, a singular vibration that transcends tonal distinctions. This is the case, for example, in the fabrics created in the 18th century by Antoine Janot, a dyer from Occitania. While they embodied all the colors of the spectrum, from the softest pink to the most intense black, they all emanate a softness, a fullness, that is the hallmark of Antoine Janot’s work. The color charts used by Lyon silk manufacturers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries can convey a similar sense of coherence, as they are the product of equally exceptional expertise.

This infinitely precious and infinitely sensitive universe was first wiped out in the industrial nations of the world, then all over the planet, when in the 20th century chemistry flooded the industry with synthetic dyes and pigments that were too often flat and inert. Today, it survives only in companies aiming for excellence and in exceptional, singular practices.

One example is Sylvie Johnson’s work. Her textures and colors speak to the skin as well as the soul, as they transmit and continue an epic of colored textiles born at the same time as humanity. They communicate the thickness of the world, but also a deep gratitude for the innumerable gifts the universe offers us.

Her instinctive yet skillful interweaving of threads, reliefs, and nuances springs from an immemorial infusion. Her works are the product of a memory constantly nourished by landscapes, art, readings, music, and encounters…

And ancient color charts, a privileged source of inspiration from which Sylvie Johnson draws for a chromatic and sensory deployment within her rich sensory landscapes. These color charts speak of color, a jewel that, in the West, has sometimes been scorned. They are based on samples, modest fragments (nothing can be done with them, and what’s more, they are fragile). What’s more, color charts reflect craft practices whose intelligence and talent have long been downplayed. Color charts are thus humble to the square, or even the cube. And yet, they conceal chromatic, linguistic, historical, anthropological, and aesthetic treasures. They are the last traces of color embodied in matter, and of an approach to color in which the beauty of the nuance is more important than its colorimetric reference.

The same is true of Sylvie Johnson’s colors. Whether given by the raw material or conferred by dyeing, they are revealed by the pertinence of their union with yarns whose nature has been precisely selected and worked upon: between weft and warp, the modes of twist are chosen for their capacity to absorb or diffract light and, in the weave, reveal the color according to the creative intention. But Sylvie Johnson’s colors also incorporate the memory and color dynamics of a company. This ability to transform the raw and integrate the perspectives of others creates the conditions for contemplation and radically new color sensations.

Sylvie Johnson’s pieces are thus powerful extracts from a fertile humus, sedimented and then one day metabolized to emerge and meet other memories, those of the people who wished these rugs to exist and those of the people who will live in their presence.

Handmade is a porous space where human intention can unfold and materials, fibers, and tools can express their truth. For Sylvie Johnson, it’s a question of perpetuating the original impulse towards beauty, of reviving it, of revitalizing the hope embodied by the universe in its multiple forms. Even, and above all, in everyday objects. Sylvie Johnson’s rugs, for example, are designed to inhabit a space and nurture a silent dialogue with its occupants. Their colors are also nurtured by chiaroscuro and the shifting light that ranges from morning to night, the subtle variations that can make a dark color brighter than the lightest shade. The light contained in colored matter expresses itself: transparency, opacity, shine, matteness, hollows, and reliefs all contribute to a harmony, in terms embodied by a complete form; advancing by subtracting, moving towards discretion, simplicity, essence, towards a poetry and beauty that provide energy and calm, as if it were self-evident.

In the hands of artists, color becomes a conduit for millennia of memory, as well as for scholarly and sensitive memory, and for a singular creative impulse. This transmission remains an irreducible but active mystery. When color responds to the call of the living and perpetuates it, it continues the link with the past, and in turn becomes a link for the present and the future. It transmits the plenitude that beauty confers, and exudes a profoundly free joy.

The experience to which Sylvie Johnson invites us is part of these links from the depths of time. It is both an echo of ancient times and a concentration of spaces where what she calls “the sap of places” is elaborated. In other words, the colors born of the vegetation of singular regions, such as the marvelous garden she is developing in Menorca. The adventure is about to unfold.