Musée des Arts Décoratifs

In 2018, Sylvie Johnson’s Atelier journey began with Bauhaus — a series rooted in the belief that art, craft, and design are not separate disciplines, but part of a unified language. To photograph this inaugural collection inside the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris was to situate it within a lineage that has long championed that very ideal.

Founded in 1864 by industrialists, artists, and collectors who believed that beauty belonged within everyday life, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs was created to elevate the applied arts. At a time when painting and sculpture dominated cultural prestige, the museum insisted that furniture, textiles, metalwork, ceramics, and industrial design were equally worthy of intellectual and artistic recognition. It presented the decorative arts not as secondary to fine art, but as essential cultural expressions — objects through which societies think, build, and understand themselves.

Housed within the Louvre’s western wing, the museum today traces the evolution of material intelligence. Its galleries move fluidly from medieval craftsmanship to modernist experimentation, presenting a continuum rather than a hierarchy. Here, material innovation and aesthetic ambition are inseparable. The decorative arts are not decorative at all — they are evidence of how societies think, build, and understand themselves.

This philosophy would find one of its most radical expressions in 1919, when Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus school in Germany. The Bauhaus proposed a transformative idea: that the artist and the craftsman were one and the same. Workshops replaced isolated studios. Collaboration replaced hierarchy. Geometry, rhythm, and material experimentation became tools for shaping a modern world. The goal was not to discard the past, but to build upon it — to fuse inherited skill with contemporary vision.

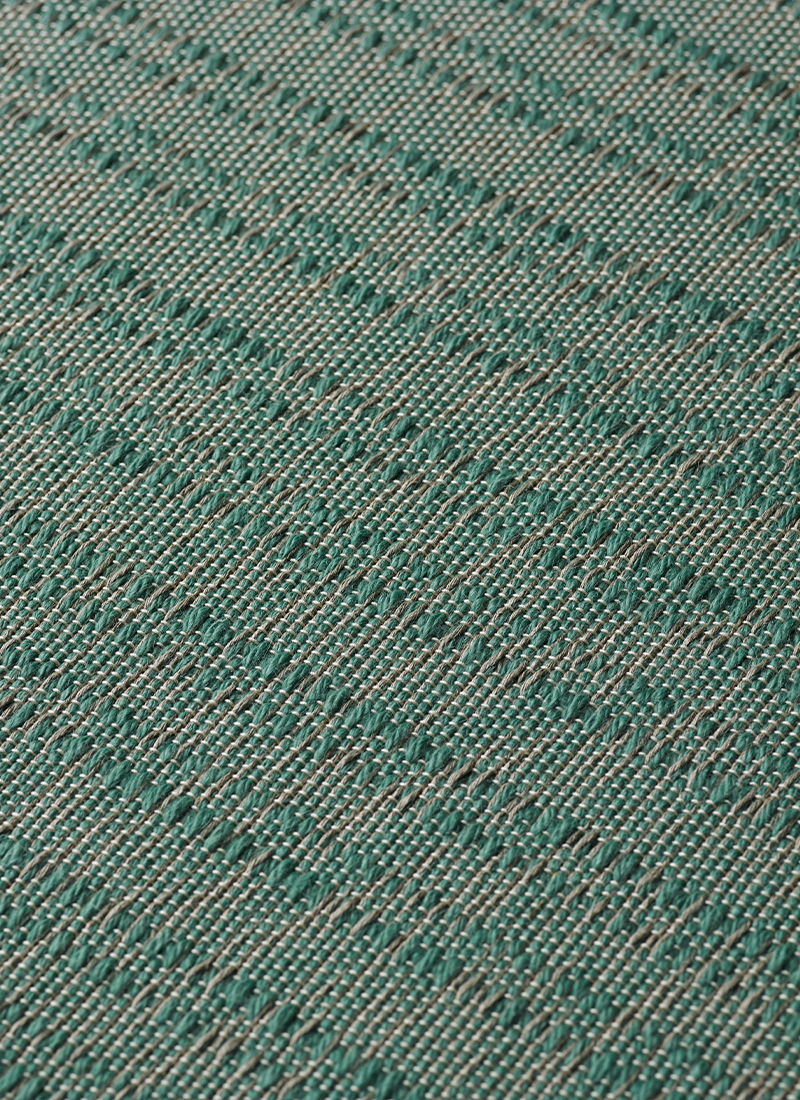

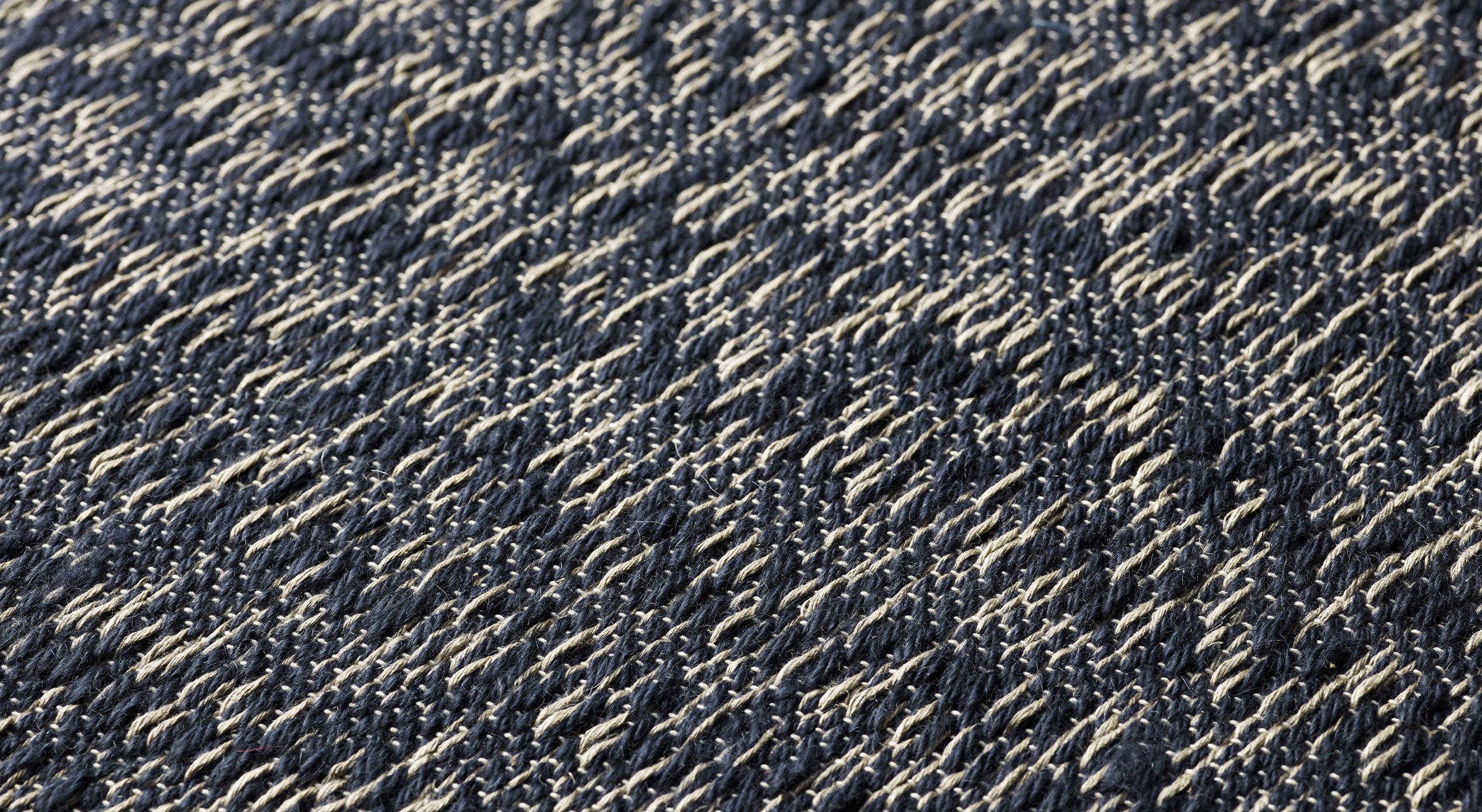

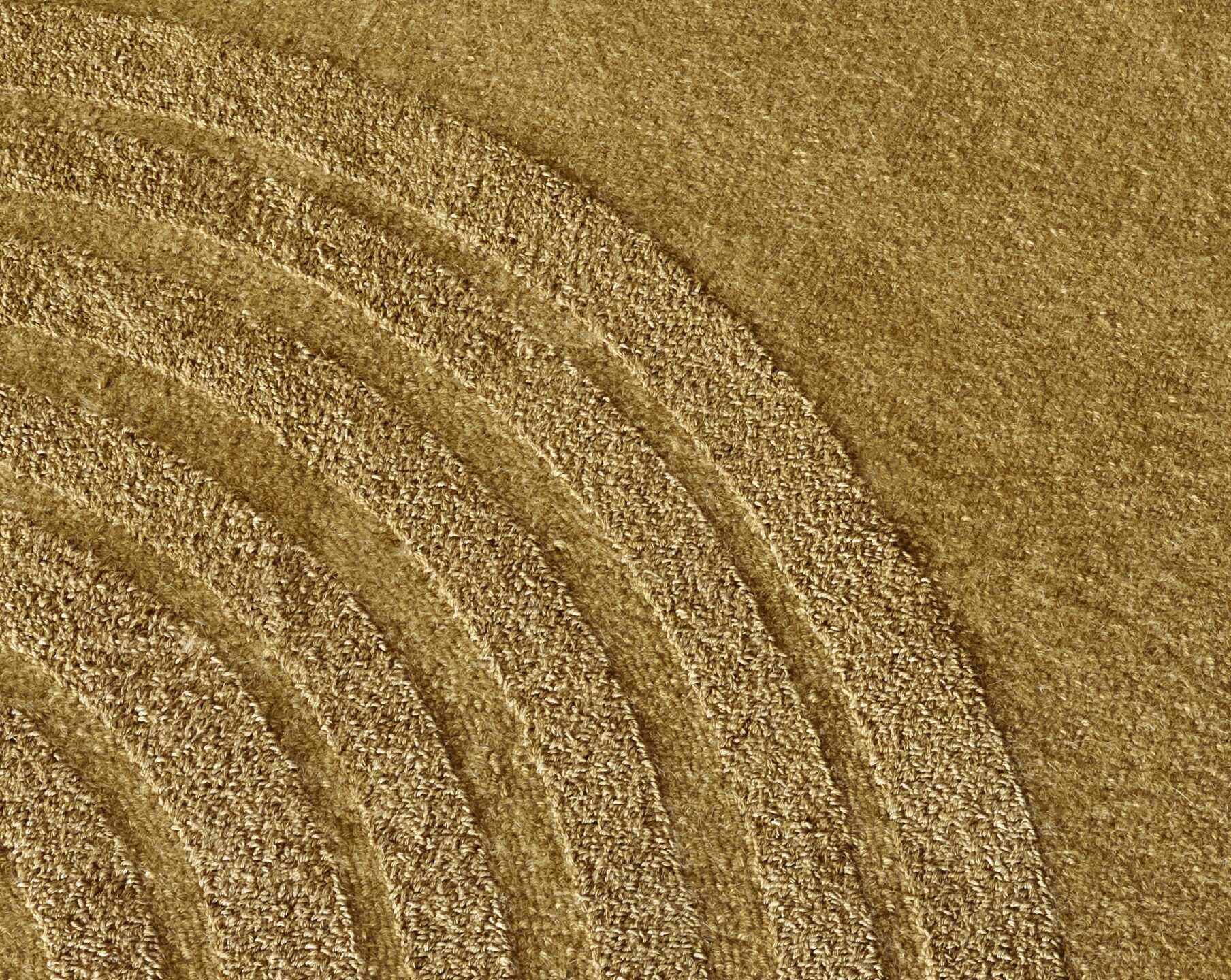

Johnson’s Bauhaus, the first chapter of the Atelier series, carries this ethos forward. In close collaboration with Merida Studio’s artisans, she approached weaving as the Bauhaus weavers once did: experimentally, rigorously, and with reverence for the hand. The geometry embedded in the series’ weaves echoes the structural clarity of Bauhaus principles. The collaborative process behind their making mirrors the workshop model that defined the school itself. Each technique, material shift, and structural decision contributes to a larger vision. The result is neither purely art nor purely design, but a living intersection of the two.

For Merida Studio, 2018 marked more than the beginning of a collection — it marked a turning point.

Fall River, Massachusetts, where Merida Studio’s workshop is based, was once one of the great textile manufacturing centers of the Industrial Revolution. Merida Studio was born within that legacy of craft. For decades, the studio was defined by technical precision and material discipline. But with Johnson’s arrival, something shifted. The workshop did not abandon its history; it leaned into it. Craft did not disappear in favor of bold artistic gesture — it deepened. The inherited discipline of weaving became the structure through which experimentation could unfold—and the vision of artistry gave this rigor direction.

It is fitting that this new chapter bore the name Bauhaus. The original Bauhaus looked forward while standing firmly on the foundation of skilled making. It sought to unify art, craft, and industry in service of a new future.

Similarly, the Bauhaus series of 2018 marked the moment Merida Studio turned its focus toward evolving the heritage of weaving in Fall River—not merely for preservation, but to elevate the practice into something greater. The ambition was clear: to create textiles that were impactful as they were beautiful. Catherine Connolly, owner and director of the studio, knew that this could not be done with craft alone but would require the vision of an artist.

Photographing the series inside the Musée des Arts Décoratifs placed this transformation within a broader historical arc. The museum’s galleries hold centuries of objects that once redefined their fields. Within its architectural grandeur and curated timelines of craft evolution, Johnson’s rugs were framed not simply as contemporary works, but as participants in an ongoing discourse — works that understood craft as a living language rather than a fixed tradition.

The Musée des Arts Décoratifs exists because its founders believed that the applied arts shape culture. The Bauhaus movement expanded that belief into a modernist manifesto. In 2018, Merida Studio embraced it as a path forward.

Bauhaus was not only the beginning of a collection. It was the beginning of a new identity — one in which weaving in Fall River would be recognized not only as skilled craft, but as contemporary art.