In Praise of Friction

We tend to think of pleasure as something lofty—music, travel, art—but some of our most sustaining pleasures are far more immediate. They live at the surface. The weight of a wool blanket across the lap. The grain of an oak table. The cool steadiness of stone under bare feet. These are small encounters, but they recalibrate us.

Touch is our first language. Long before we could name the world, we pressed our palms into it. It is the earliest sense to develop—our first form of orientation, our first reassurance that we are held. That early education never leaves. There is something innate in our response to texture: some surfaces we seek instinctively; others we recoil from without knowing why. We want our sweaters and bedding to be soft and pliant, plush enough to echo the memory of being swaddled—warm, contained, safe. In different contexts, we search for different textural signals, reading them for what they can tell us, for what they promise.

When we reach for natural materials—solid wood, cotton, wool, clay—we are not only making an aesthetic choice. We are responding to signals our bodies recognize. Natural fibers hold variation: a slight irregularity in spin, a change in density, a softness that deepens with time. Wood carries grain that resists uniformity. Stone shifts temperature throughout the day. These subtleties create a quiet complexity the mind does not tire of. Think of watching waves or a burning fire—seemingly constant, yet constantly changing; hypnotic. Even brief contact with textured, organic surfaces—tree bark, grass, rough stone—has been shown to lower stress. The body softens. The breath deepens. We return to scale. Touch grass? It is no wonder it’s a rallying cry of the modern age.

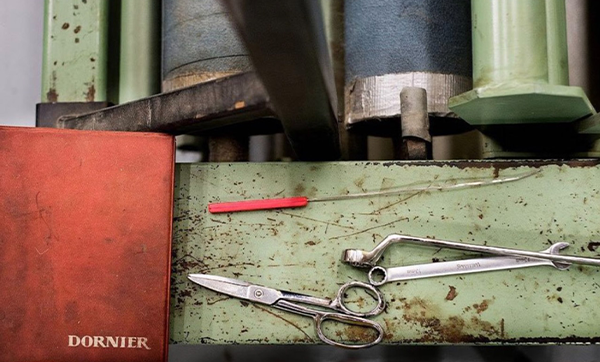

We are more perceptive than we realize. When we encounter a material shaped by time and hands, we register it. A carved wooden table carries subtle undulations from the tools that formed it. A hand-thrown ceramic bowl wavers almost imperceptibly at the lip. A knitted sweater contains the rhythm of its making. Even if we cannot articulate these details, our bodies sense depth. Variation signals life. Weight signals substance. Slight irregularity signals life. Does every tree grow identically? Uniformity may be predictable, but imperfection feels alive.

In our modern world, much has become slick. Minimalism, in its broadest commercial translation, often smooths the edges of experience. Corners are rounded; surfaces are lacquered into sameness; risk is mitigated. Safety is, of course, essential—but the safest imaginable environment might be a sterile bubble. Is that the most fulfilling way to live? I suspect not. Variation is how we navigate. If every surface were identical—uniform in color, weight, temperature—how would we distinguish a tree from a skyscraper, a river from a road?

Textures deliver information. Moist soil tells us it rained. Lichen clinging to a stone wall signals time, patience, heritage. A wooden stair smoothed by decades of footsteps bears witness to those who passed before. We are fluent in this language, even if unconsciously. Even department stores understand it, arranging vignettes not just by color but by texture—chunky knits draped over sofas, ribbed ceramics beside matte wood frames. Texture signals quality and craftsmanship. A knit sweater announces its own making; the rough grain of wood implies a tree once stood, shaped by practiced hands into form.

Psychologists who study sensory experience note that textured, natural environments reduce stress and improve focus. We relax more readily in spaces that offer tactile richness—woven rugs, solid wood, natural light—than in spaces composed entirely of slick, reflective surfaces. It is not nostalgia; it is regulation. The body prefers information it can read and relate to. We may forget that we are part of the natural world, but our bodies do not.

There is also pleasure in resistance. A surface that pushes back slightly—a dense wool, a sturdy cotton canvas—reminds us of our own physicality. We feel our strength in relation to it. Smooth plastic offers no dialogue; it slides past us. Natural materials meet us halfway. They absorb warmth from the palm, moisture from the air. They respond.

To seek out these materials is not indulgence for its own sake. It is an investment in emotional steadiness—in surrounding yourself with a world that talks back to you.

None of this requires grand gestures. It might mean taking your shoes off more often. Choosing a wool throw over a synthetic fleece. A cotton shirt that grows softer with each wash instead of one that pills and thins. Over time, these choices accumulate. They shape the sensory atmosphere of our lives.

We live in an era that prizes sleekness and efficiency. But we are not sleek creatures. We are textured. Our skin reads nuance. Our nervous systems respond to warmth, weight, and variation. When we surround ourselves with materials that echo those qualities—materials that age, breathe, and bear the trace of making—we are, in a quiet way, caring for ourselves.

There is pleasure in tactility because it is how we first explored the world as blurry-eyed infants, and it is how we continue to explore it now. When I lie in grass, my body releases into the ground—a full-bodied sigh. When I run my palm along a wooden table, I sense a warmth absent from a plastic folding chair. Texture is not decoration. It is orientation. It is memory. It is belonging.

In a world that grows ever smoother, perhaps pleasure lies not in erasing friction but in embracing it—in allowing the grain to show, the fibers to prickle, the seasons to press against us. To live fully is not to inhabit a bubble, but to remain in contact.